There's a term that's been bandied about the English teacher community for as long as I've been a part of it (and probably longer): authentic audience. It's the notion that when students write, they should not be writing for an audience of one: namely, their teacher. They should not just be writing in order to get a passing grade and keep their parents off their case. Students should be writing for an authentic audience, an audience that has a legitimate interest or stake in what is being written. This gives purpose and authenticity to the task; it helps students see meaning in their work and it helps transfer their skills to the larger world outside of school.

So, in the last installment of my trilogy of blogposts about my collaborative class novels, I'm happy to report that my students not only had an authentic audience for their novel but had the opportunity to meet and interact with readers, face-to-face.

What exactly happened, you may ask? Last month, my own book club (my off-hours reading self) held its September book club meeting in the auditorium of the high school where I teach. When I'd mentioned our novel writing to my book club last spring, several friends suggested we read it as a book club choice, and the seed for an authentic audience was planted. Four months later, my student authors had the opportunity to meet their readers and hear what community members think of the novels they published. Sophomores now, they were no longer in my class, but most attended anyway (more signs of authenticity).

What exactly happened, you may ask? Last month, my own book club (my off-hours reading self) held its September book club meeting in the auditorium of the high school where I teach. When I'd mentioned our novel writing to my book club last spring, several friends suggested we read it as a book club choice, and the seed for an authentic audience was planted. Four months later, my student authors had the opportunity to meet their readers and hear what community members think of the novels they published. Sophomores now, they were no longer in my class, but most attended anyway (more signs of authenticity).

|

| Our Book Signing event in May |

The prospect of having my book club read my class novels and interact with my students admittedly made me a bit anxious, as is always the case when the personal and the professional intersect in my life. However, five minutes into the event, it was apparent that this was the perfect icing on the cake for our novel writing experience. Students were excited to know that members of their own community read and enjoyed the novels they wrote, and community members were overwhelmingly impressed with the depth and quality of the student chapters.

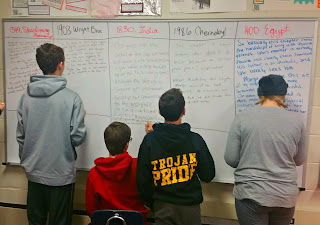

One of my book club friends, a voracious life-long reader, told my students to keep writing, and that some are clearly on their way to becoming professional novelists if that's the path they choose. My students were asked how they came up with their ideas, if their characters were echoes of their own beliefs, if they looked at history and the world differently, having now researched and written about teen's lives in history. The answer was a profound "yes," hitting me in that deep down teacher-satisfaction place. Students asked their readers about the effect of the book's format and its multiple authors, and checked to see if their readers had detected the thematic threads they wove into the story and subtle references they embedded (they had!).

The interactions were rich and....authentic. I allotted one class period, but clearly it could have been two as students reluctantly returned to class when the bell rang (after being given a standing ovation by my book club). I received an email from a book club member that night raving about the experience and admitting that 1) they had ice cream without me 2) over ice cream, they continued talking about the books and what an incredible experience the event had been.

My take-aways?

- I feel like I now finally understand what a truly authentic audience is: how dynamic it is, how rare it is, and how valuable it is.

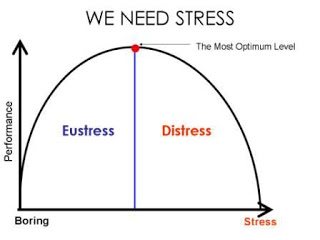

- I am reminded (time and again) that anxiety in teaching, for me at least, is always a good sign. It means I'm stretching myself and broadening my students' experiences.

- Writing a collaborative class novel was worth the effort. The experience continues to pay dividends for my students; and so, I'll keep doing it.

More information about the novels can be found on our Novel Website.

Lately, I’ve been feeling anxious, I’ve been losing sleep, I’ve had daily, probably hourly misgivings. And yes, I’m a teacher, so this is all a bit par for the course, but I’ve been teaching for 24 years--- I should be well past the nervous, sleepless, anxiety-ridden stage.

Lately, I’ve been feeling anxious, I’ve been losing sleep, I’ve had daily, probably hourly misgivings. And yes, I’m a teacher, so this is all a bit par for the course, but I’ve been teaching for 24 years--- I should be well past the nervous, sleepless, anxiety-ridden stage. So how DOES one write a class-sourced novel? In a nutshell, Jay Rehak’s method (generously shared and clearly explained in his

So how DOES one write a class-sourced novel? In a nutshell, Jay Rehak’s method (generously shared and clearly explained in his