I’ll be sharing a right of passage with my son this year: he’ll be entering high school, and in a few short weeks, I’ll be his teacher. (I suspect you’ll be reading a post or two about how that goes!) He’ll also face another transition as he leaves behind 11 years of Montessori and takes his first step into public education, a slew of new beginnings for mother and son.

Wait, did you catch that? You might want to re-read the previous paragraph because couched among some fairly cliche sentiments about rights of passage was a raw admission. Did you detect the hypocrisy? Did you smell the sacrilege? A public school teacher blogging all this time about public education while sending her own child to a Montessori school! The shame!

I remember the first time I tried to explain it to someone. I was on lunch duty, standing next to a colleague and friend of mine who asked where Eliot would be going to school. He was maybe 5 at the time. “He’ll keep going to Nature’s Classroom Montessori for now,” I remarked, going on to explain how we had never planned on sending him to a private school, but that because Montessori had been such a perfect fit for him, we couldn’t imagine pulling him from a place that had become home. I explained how I felt hypocritical about it as a public school teacher who believes in public education. I added, hoping for redemption, that he would likely be coming to our high school when the time came. She laughed at my very long and defensive answer. “Sounds like the perfect place for him," she said and meant it. I exhaled.

It’s true that Eliot has the questionable fortune of being born to two public school teachers. It’s true that we never planned on going the Montessori route. It’s also true that initially we felt like traders sending him to Montessori over our local school district. See, here’s what happened: when Eliot was 3, counting ceiling tiles when we picked him from daycare, it was clear he was ready for a more challenging environment. When a friend told us about Nature’s Classroom Montessori, we went for an observation and never left.

That day, we observed Miss Erin’s room, which we quickly dubbed “The Zen Room.” It was an amazing sight: 3, 4 and 5-year-olds manipulating objects to learn numeric concepts, tracing and placing alphabetic letters into stories, preparing their own snacks, cleaning their work spaces. The level of independence and engagement was astounding. It was an environment in which Eliot soon thrived.

As parents and as teachers, what we saw that day was what we both had struggled to create in our own classrooms: independent learners fully engaged and invested in their own learning. And what we saw wasn’t the doing of an individual teacher; it was the systemic use of Montessori methods in the Montessori environment. We were in awe.

We watched Eliot’s first class concert later that year. As his classmates proudly belted out their songs, some clapping, some waving to their parents, there stood Eliot, not saying or singing a word. When we talked to his teacher afterwards, she was not at all concerned. He’ll come around when he’s ready, and she was right. And that’s what it his Montessori experience has been like: we’ve watched him grow through the years from a non-singer to concert emcee his final year. This was a school where his social-emotional well being was as important as his academics: through the years we all worked (teacher, parents, and Eliot) on his ability to work in groups, take responsibility for his actions, and organize his work.

We watched Eliot’s first class concert later that year. As his classmates proudly belted out their songs, some clapping, some waving to their parents, there stood Eliot, not saying or singing a word. When we talked to his teacher afterwards, she was not at all concerned. He’ll come around when he’s ready, and she was right. And that’s what it his Montessori experience has been like: we’ve watched him grow through the years from a non-singer to concert emcee his final year. This was a school where his social-emotional well being was as important as his academics: through the years we all worked (teacher, parents, and Eliot) on his ability to work in groups, take responsibility for his actions, and organize his work.

How could we pull him from Montessori? We couldn’t, and didn’t. It was simply the best place for him. Maria Montessori said “One test of the correctness of educational procedure is the happiness of the child.” And by that measure, he wasn’t going anywhere.

You may be asking yourself What exactly is Montessori? Here’s a crash course: In the early 1900’s Maria Montessori, an Italian physician studied children who had been deemed non-learners. Through careful observation, she created an environment in which they thrived. Her method, now known as Montessori, provides flexible and carefully constructed work space and materials, utilizing a constructivist philosophy where children engage in “practical play,” learning through discovery with teacher guidance rather than direct teacher instruction.

I asked Eliot today what Montessori did for him. “It made me, me,” he said, with an implied “duh!” (he is 14 after all). Details that stick with him? Journaling in nature. Being farm manager. Playing William Shakespeare. Studying marine biology in the Florida Keys, and indigenous cultures in New Mexico. Explaining the cube of quadrinomials. Historical simulations. Writing and acting in plays. His magnum opus paper.

I asked Eliot today what Montessori did for him. “It made me, me,” he said, with an implied “duh!” (he is 14 after all). Details that stick with him? Journaling in nature. Being farm manager. Playing William Shakespeare. Studying marine biology in the Florida Keys, and indigenous cultures in New Mexico. Explaining the cube of quadrinomials. Historical simulations. Writing and acting in plays. His magnum opus paper.

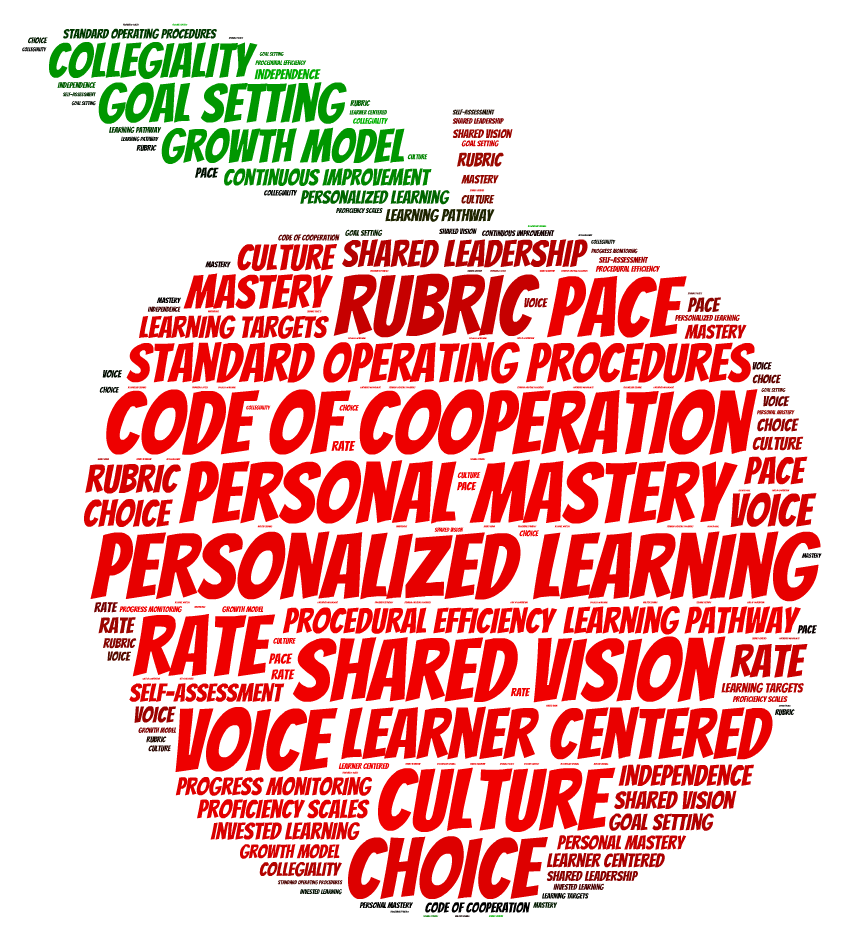

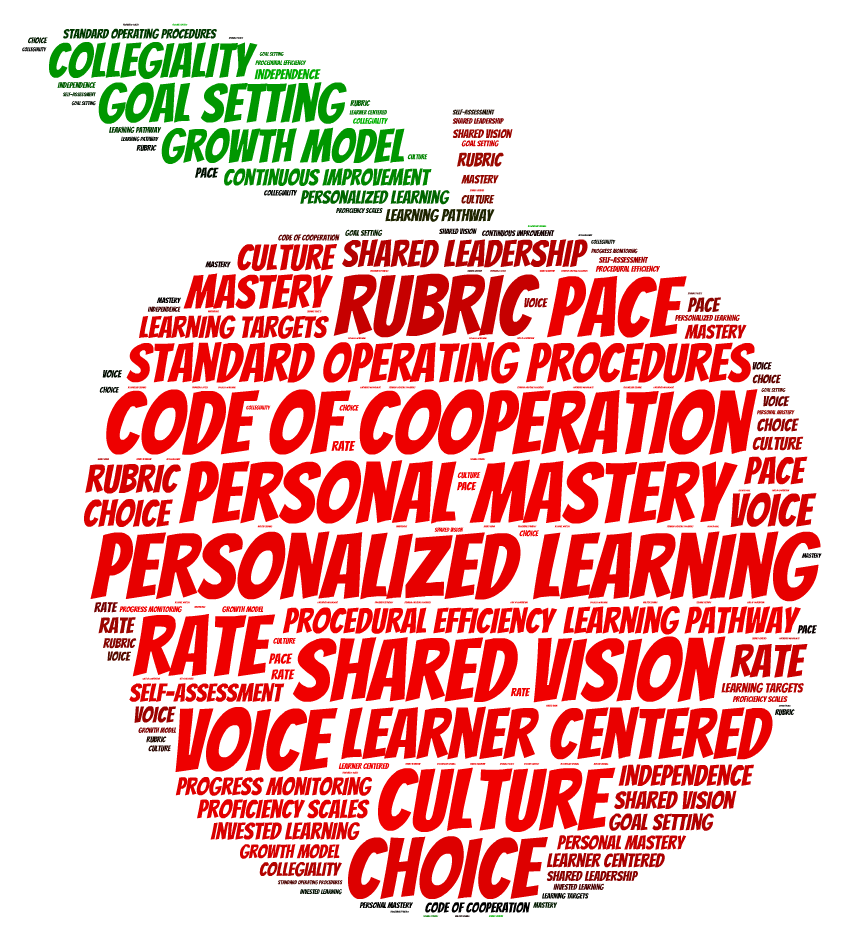

So here’s the strange part, where past meets present, alternative meets traditional, mother meets son. Any teacher or administrator in education today will recognize the following buzzwords (causing some perhaps to shudder a bit): personalization, student-centered classroom, problem-based learning, standards-based grading. Open any educational journal or attend any educational conference, and these words will dominate the articles written and the sessions offered. These concepts---here’s the weird part---are and always have been evident, in mastery form, in the Montessori classroom. They are the  reasons my husband and I were in awe that day when we observed “The Zen Room.”

reasons my husband and I were in awe that day when we observed “The Zen Room.”

reasons my husband and I were in awe that day when we observed “The Zen Room.”

reasons my husband and I were in awe that day when we observed “The Zen Room.”

The truth is Montessori has much to teach us. As a teacher, It is my hope that as personalization, student-centered classrooms, and problem-based learning continue to be examined, the best of Montessori will trickle into the public school realm. As a mother, it is my hope that they will continue to be part of Eliot’s high school experience in my classroom and others.

Ready or not, Eliot, here we go.